Metaprogramming is a very specific technique in software development in which a portion of code treats other code as its data. Weird, right? This article is about to put a light on that concept using ES6 Proxy.

Proxies are an essential part of all modern front-end frameworks and a key to data reactivity (e.g., Vue 3). If you haven't heard of Javascript Proxy yet, here's a bit of explanation. You can treat Proxy as a wrapper that wraps around the target object. You will use that wrapper throughout the code instead of the target object itself. Basically, the wrapper receives all the passed data and have the control of the object inside over the handler object methods.

In the following example, the wrapper will behave identically as the target, because the handler object is empty.

const target = {

sayHi: () => console.log('Hello World!')

}

const handler = {}

const wrapper = new Proxy(target, handler)

wrapper.sayHi()Console output:

Hello World!See, nothing weird happened. Now let's add a method get to our handler and look what will be the output when we "say hi" again.

const target = {

sayHi: () => console.log('Hello World!')

}

const handler = {

get(target, prop) {

console.log(`You want to call "${prop}" method on the target object.`)

return Reflect.get(target, prop)

}

}

const wrapper = new Proxy(target, handler)

wrapper.sayHi()Console output:

You want to call "sayHi" method on the target object.

Hello World!This time we have two logs in the console. One log comes from our get handler and it is executed before the saiHi method.

Handler methods are also called traps — probably because they trap passed arguments and control the further flow of data. We will need to reflect received arguments in order for target object to perform its original behavior. In essence, Reflect should use the same handler method and call a target function (from the target object).

This is a very basic explanation covering only get trap, but I believe it will be sufficient for you to understand what we're about to create by the end of this article. However, if you're looking for something thorough, check out the MDN docs on Proxies.

Creating an Interceptor Using Javascript Proxy

We're going to create class Interceptor, so we can easily inherit the functionality wherever we need to intercept any method call throughout the app. The constructor accepts options object which contains array of methods-to-watch and a beforeMethodCall function which is basically a code block with "stolen" data that executes before the original method.

I am using JSDoc to somewhat increase readability by pointing out types of the parameters. Hope it's helpful!

class Interceptor {

/**

* @param {Object} options

* @param {String[]} options.watchMethods

* @param {Function} [options.beforeMethodCall]

* @return {Proxy}

*/

constructor(options) {

return Interceptor.#proxy(this, options)

}

static #proxy(obj, options) {

return new Proxy(obj, {

get(target, prop) {

if (typeof target[prop] === 'function' && options.watchMethods.includes(prop)) {

return new Proxy(target[prop], {

apply(target, thisArg, argumentsList) {

options.beforeMethodCall(prop, argumentsList)

return Reflect.apply(target, thisArg, argumentsList)

}

})

} else {

return Reflect.get(target, prop)

}

}

})

}

}

export default InterceptorAs you probably noticed, a Proxy with a get trap is wrapped around a Proxy with an apply trap. We cannot get arguments using a get trap alone, because the target function is not called at that time.

Inside the apply trap, you will notice highlighted beforeMethodCall function that is being executed right before reflecting all the arguments. In today's example, we are not mutating any arguments that beforeMethodCall receives, instead we're just going to use them as readable data and pass them along intact.

However, if you want to mutate arguments before passing them to the target object, you would need to return mutated arguments from the beforeMethodCall and then reflect them on the argumentsList position.

How to Use Interceptor Base Class

Very simple — just extend the Interceptor and inside the super pass the options which will include an array of method names you want to watch for and a beforeMethodCall with your functionality. I am using a static property to keep objects within the class, but you are free to displace this object outside and pass it through the constructor. Whatever works for you (the beauty of Javascript).

As you may notice in the example below, Interceptor monitors 4 out of 6 of its methods in the Dom class.

import Interceptor from './Interceptor.js'

class Dom extends Interceptor {

static options = {

watchMethods: ['mount', 'registerConsole', 'registerButton', 'consoleLog'],

beforeMethodCall(name, args) {

if (

['mount', 'registerConsole', 'registerButton'].includes(name) &&

!(document.querySelector(args[0]) instanceof HTMLElement)

) {

throw new TypeError(`Please pass the query selector of an HTML element to the ${name} method.`)

}

switch (name) {

case 'mount':

console.log(`The app will mount on root "${args}".`)

break

case 'registerConsole':

console.log(`The console will be registered on root "${args}".`)

break

case 'registerButton':

console.log(`The button will be registered on root "${args[0]}".`)

break

case 'consoleLog':

console.log(`New HTML output log at ${new Date().toLocaleString('en-GB')}:`, ...args)

break

}

}

}

/**

* @param {Array} components

*/

constructor({ components }) {

super(Dom.options)

this.components = components

this.root = undefined

this.consoleRoot = undefined

this.buttons = {}

return this

}

/**

* @param {String} root

*/

buttonElement(root) {

return this.buttons[root]

}

/**

* @param {String} root

*/

mount(root) {

this.root = document.querySelector(root)

this.root.innerHTML = this.components.map((component) => component.html).join('')

console.log('The app is mounted.')

return this

}

/**

* @param {String} root

*/

registerConsole(root) {

this.consoleRoot = document.querySelector(root)

console.log('The console is registered.')

return this

}

/**

* @param {String} root

* @param {Function} handler

*/

registerButton(root, handler) {

this.buttons[root] = document.querySelector(root)

this.buttons[root].addEventListener('click', handler)

console.log('The button is registered.')

return this

}

We are going to pay attention to the highlighted log and consoleLog methods, because the former is not being monitored and both of them are used in our event handlers:

- Regular Button:

app.log(...)- prints out the text on the screen. - Super Spy Button:

app.consoleLog(...)- prints out the text in the console with a timestamp and then on the screen.

// main.js

import Dom from './core/Dom.js'

import AppButtons from './components/AppButtons.js'

import ConsoleOutput from './components/ConsoleOutput.js'

const app = new Dom({

components: [AppButtons, ConsoleOutput]

}).mount('#app')

app

.registerConsole('#output')

.registerButton('.super-spy-btn', handleSpyBtn)

.registerButton('.regular-btn', handleRegularBtn)

function handleSpyBtn() {

const btnColor = handleBtn('.super-spy-btn', 'red')

app.consoleLog(`The button is now ${btnColor}.`)

}

function handleRegularBtn() {

const btnColor = handleBtn('.regular-btn', 'orange')

app.log(`The button is now ${btnColor}.`)

}

function handleBtn(btnSelector, btnColor) {

const btnClassList = app.buttonElement(btnSelector).classList

btnClassList.toggle(btnColor)

if (btnClassList.contains(btnColor)) {

return `<span class="text-${btnColor}">${btnColor}</span>`

}

return '<span class="text-blue">blue</span>'

}The Interceptor in Action

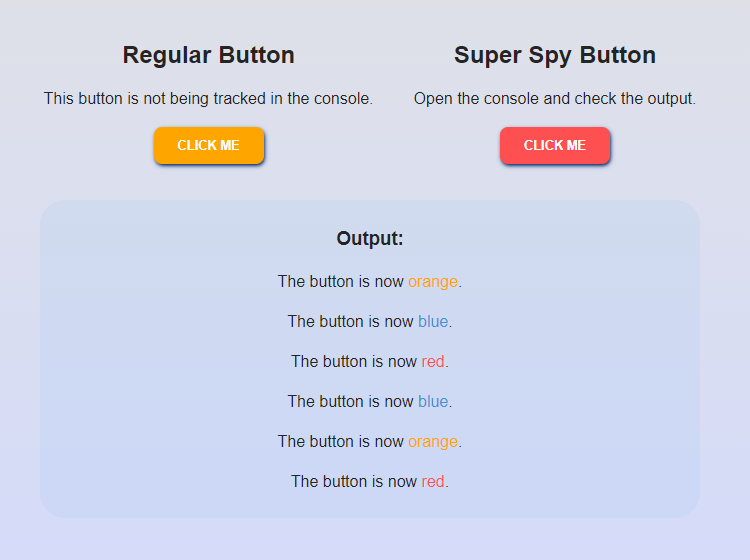

I've scrambled up a simple vanilla Javascript app using Vite as a dev server (repo is linked at the bottom of the article). It is a one-pager that contains two buttons and the HTML output area.

Each button is clicked three times. You will notice there are 6 click registered in the output and only 3 clicks in the console (with a timestamp) that come from the Super Spy Button.

Console output:

The app will mount on root "#app".

The app is mounted.

The console will be registered on root "#output".

The console is registered.

The button will be registered on root ".super-spy-btn".

The button is registered.

The button will be registered on root ".regular-btn".

The button is registered.

New HTML output log at 23/09/2022, 17:39:55: The button is now <span class="text-red">red</span>.

New HTML output log at 23/09/2022, 17:39:56: The button is now <span class="text-blue">blue</span>.

New HTML output log at 23/09/2022, 17:40:00: The button is now <span class="text-red">red</span>.Pretty cool, right?

Applications of Proxy Interceptors

Form validation is a great example. Trapping and validating data in a separate code block seems like a neat way to keep the technical stuff separate from the business stuff in a project.

You may have also heard of HTTP client's request and response interceptors (e.g., Axios), which are mainly used for updating token in request headers and preparation of response messages. Well, they don't use Proxy. However, a front-end dev named Dennis wrote a very cool blog post on Divotion in which he provided the very same yet cleaner implementation using Javascript Proxy.

Other use cases could be caching, logging events and/or errors, you name it! Whatever requires pre or postprocessing in runtime, Proxy interceptor is your savior.

Wrapping Up

I hope you have learned something that will help you become a better Javascript developer, or perhaps found a code error I made along the way. Either way, let me know about your feedback.

If you have any ideas of how this little Interceptor can be useful in a real-life application, please don't hesitate to type a comment. And don't forget to check out the live demo. 👋😉

Live Demo and Code

Live demo: https://lazarkulasevic.github.io/javascript-proxy