A relatively young approach to development – trunk-based development (TBD) – has come out as a result of seven years of research and data from over 32,000 professionals worldwide, conducted by DORA State of DevOps. It is the longest-running academically rigorous research investigation of its kind, providing an independent view into the practices and capabilities that drive high performance in technology delivery and ultimately organizational outcomes.

The research uses behavioral science to identify the most effective and efficient ways to develop and deliver software. It proved to be a great approach and engineers seem to love it. Many teams have adopted TBD so far. Just to name a well-known few, there is a Github team that works on github.com, Visual Studio Team Services, Google and Netflix.

TBD: Overview

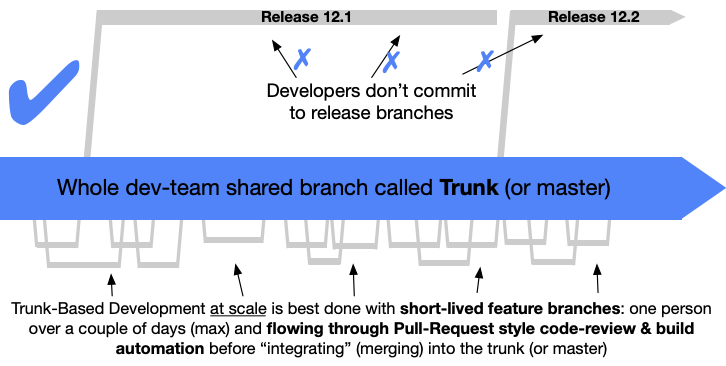

By definition, trunk-based development is a git branching strategy that emphasizes the use of a single, shared code repository or "trunk" where all developers work on the same codebase. Rather than branching off separate copies of the code for each feature or bug fix, developers make changes directly to the main trunk, which is continuously integrated (CI) and continuously deployed (CD) to production.

trunkbaseddevelopment.com

TBD vs Gitflow

Let’s make a brief comparison with the all-timer branching strategy – Gitflow. It uses at least two long-lived branches, main and develop. Feature branches are created off develop and merged back when completed, after which they usually keep living in the project.

Sometimes when changes are tested and testing fails, it would become increasingly difficult to figure out where the issue is exactly as developers are lost in a sea of commits. All of this could slow down the development process and release cycle. In that sense, gitflow is not an efficient approach for teams wanting to implement CI/CD.

Unlike Gitflow, TBD uses one and one only long-lived branch, main, off which short-lived feature branches are created. After the work is done on a feature branch, commits are squashed and merged as a single commit and the feature branch is deleted afterward. This enforces linear commit history.

Giflow provides more structure than TBD, but can be complex to manage and sometimes can lead to merge hell.

TBD: Pros and Cons

TBD is designed to promote collaboration, reduce complexity, and accelerate development cycles by eliminating the overhead of managing multiple branches and merges. By working directly on the trunk, developers can quickly integrate and test changes in a shared environment, which can help catch and resolve issues early in the development process.

However, there are a few unwanted risks that come along with the TBD. For instance, there is a risk of introducing breaking changes. Because all developers are working on the same codebase and changes made to the trunk can potentially break the existing code or cause conflicts with other changes. Nevertheless, this risk can be avoided by simply configuring some branch protection rules, especially the one that prevents merging branches that are not up to date with the main branch.

Secondly – the need for strong communication – well, technically this isn’t a risk, but rather a “downside” if you look at communication as an obstacle. With everyone working on the same trunk, it's crucial that teams communicate well and work collaboratively to avoid conflicts and ensure that changes are integrated smoothly. This can be challenging, especially for larger or distributed teams.

Practices that define TBD

At first glance, TBD seems to be a straightforward process. That’s not far from the truth, but this perk is determined by a set of practices that has to be conducted properly in order to ease the development and conserve the beauty of straightforwardness.

- Strict coding standards

- Frequent code reviews

- CI/CD with notifications

- Automation

Depending on the project, the CD abbreviation somewhere stands for continuous delivery and somewhere for continuous deployment. Key difference is a well-known agile ceremony – The Release Day – where continuous deployment excludes the need for that step because all changes are automatically deployed to production. However, the latter requires feature flags to be set in place.

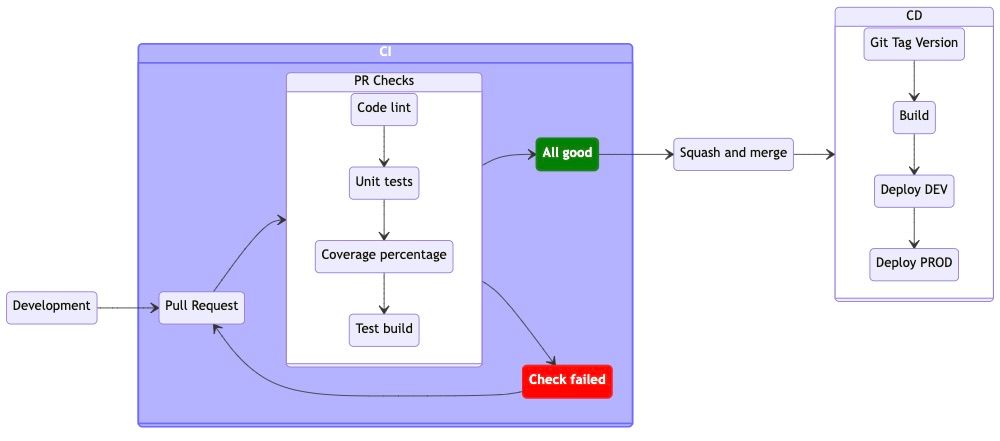

What I’ve noticed during my career is that every team that uses TBD has a slightly different approach to CI/CD. And that is totally legit. After all, this is an organizational tool that should be adjusted to teams’ needs.

For example, I have orchestrated a set of pipelines for one of our projects in a manner that excludes additional test runners in the CD part to save on Github minutes and also put a version tag before the build step. It may look a bit inconvenient, but in fact, this setting perfectly suits my team’s needs.

CI/CD Example Schema

These practices help to ensure that the code on the main branch is always in a stable, releasable state and that changes are thoroughly reviewed and tested before they are integrated. By following these practices, teams have a greater chance to produce high-quality code and ship changes more quickly to the test environment and their clients.

Building CI/CD pipelines using Github Actions

Github actions use workflows – Yaml files – located in the .github/workflows/ root directory. There are lots of open-source Github actions that you can use in your workflow and drastically speed up the development of your pipeline. For example, widely used actions/checkout@v3, checks out your repository under $GITHUB_WORKSPACE, so your workflow can access it. And there are many more, some of which we’re going to use in our workflows.

Continuous Integration (CI)

In the CI part, we are going to make sure that no “smelly” or untested code can be merged. For that to work, we will define a pipeline that will test our code along the way and notify us if there is something wrong with it upon pull request (PR) creation.

Continuous Integration (CI)

Besides the four PR checks on the graph, the workflow includes a few more steps that round up the CI. I have put all steps in a single job named Quality Check, set ubuntu as my job runner and configured a trigger to run this workflow upon PR creation.

First things first, checkout your repo. Then set environment variables in a separate step by running shell commands that extract engine versions from package.json – in this case node and pnpm – making them easily accessible within the job by simply calling env.NODE_VERSION. That way, we’re making package.json to be the single source of truth regarding engine versions. So we don’t need to update them manually through our workflows after updating them in the project.

Afterward, initiate node and pnpm with extracted versions, install dependencies and perform noted checks: lint code, Typescript check, unit tests are passing, line coverage is above 80%.

# pull-request.yml

name: PULL REQUEST

on:

pull_request:

branches:

- main

jobs:

quality:

name: Quality Check

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

uses: actions/checkout@v3

- name: Set ENV variables

id: env_vars

run: |

echo "NODE_VERSION=$(jq -r .engines.node ./package.json)" >> $GITHUB_ENV

echo "PNPM_VERSION=$(jq -r .engines.pnpm ./package.json)" >> $GITHUB_ENV

- name: Use pnpm (${{ env.PNPM_VERSION }})

uses: pnpm/action-setup@v2

with:

version: ${{ env.PNPM_VERSION }}

run_install: false

- name: Use Node.js (${{ env.NODE_VERSION }})

uses: actions/setup-node@v3

with:

node-version: ${{ env.NODE_VERSION }}

cache: pnpm

- name: Install dependencies

run: pnpm install

- name: Lint

id: lint

run: pnpm run lint

- name: TypeScript check

id: tsc

run: pnpm tsc

- name: Unit tests

id: test

run: |

pnpm run test:coverage > test_result.txt

cat test_result.txt

echo "coverage_value=$(cat test_result.txt | tail -2 | head -1 | sed 's/.*: \([0-9]*\)\..*/\1/')" >> $GITHUB_OUTPUT

- name: Unit test coverage

id: coverage

run: |

if [[ ${{ steps.test.outputs.coverage_value }} -le 79 ]]; then

echo "Code coverage is less than 80%. Try to cover more lines with unit tests."

exit 1

fiIn our project, we use Vitest for running unit tests and C8 for collecting coverage. The last step check is adjusted to these specific technologies. So if you try to reuse this workflow, make sure that you collect coverage correctly as per your technologies’ docs.

Now, we must notify the developer of the job outcome because without notifications all of this fuss somehow loses the point. And by notifications, I mean just passing the message through Github’s already built-in emailing system and creating a code coverage badge that can be displayed in the project’s readme file.

# pull-request.yml

# ...

- name: Create code coverage badge

if: success()

uses: schneegans/dynamic-badges-action@v1.6.0

with:

auth: ${{ secrets.GIST_TOKEN }}

gistID: <your_gist_id>

filename: unit-test-coverage.json

label: Coverage

message: ${{ steps.test.outputs.coverage_value }}%

valColorRange: ${{ steps.test.outputs.coverage_value }}

maxColorRange: 90

minColorRange: 50

- name: Comment the Issue (email content)

if: ${{ always() }}

uses: actions/github-script@v6

env:

BRANCH_NAME: ${{ github.event.pull_request.head.ref }}

with:

script: |

github.rest.issues.createComment({

issue_number: context.issue.number,

owner: context.repo.owner,

repo: context.repo.repo,

body: `Your HTML/Markdown content with job result.`

})And that’s it! If the job outcome is successful, Github will let you merge this PR; if not, well… you’re gonna need to fix that error and cover a few more lines with unit tests. Other than that – easy peasy.

Branch protection rules

Most importantly, the main trunk must be protected from pushing directly to the branch or merging outdated branches. In the Github repo settings, you can find a section dedicated to protecting branches. Pick the main branch and add the following rules:

- Require a pull request before merging

- Dismiss stale pull request approvals when new commits are pushed

- Require status checks to pass before merging

- Require branches to be up to date before merging

- Quality Check (Github Actions)

- Require linear history

- Restrict who can push to matching branches

- Restrict pushes that create matching branches

- Admin account (Github Actions)

- Allow deletions

Rules I would especially like to discuss are 2 and 3. The second rule prevents merging changes if the quality check is failed and the third one ensures that new commits are either squashed before merging or rebased onto the protected (main) branch. These two keep the code reliable and git history clean.

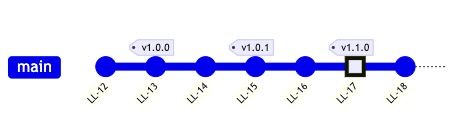

Git linear history

Git linear history

Continuous Delivery (CD)

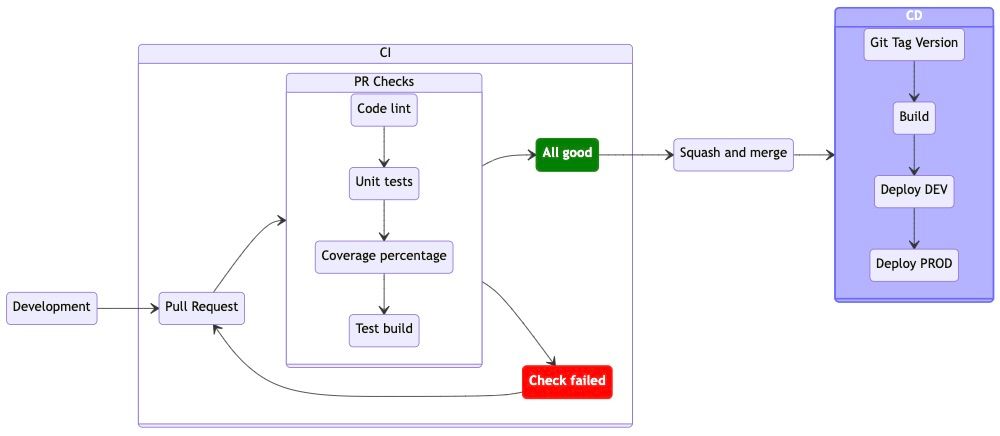

Following the same logic, with a slight advancement regarding workflow reusability, continuous delivery can be accomplished as well. Unlike the CI workflow, which handles everything in a single multistep job, CD will have separate jobs that will depend on each other’s outcome.

Continuous Delivery (CD)

Starting with bumping the version in package.json and creating a git tag for that version, then building and deploying the tagged code for development and production environments. Depending on the project, the build can be accomplished in a single step for all environments or it has to be built separately for each. In my case, each environment uses different configs, hence separate builds are required.

But first, we must get engine versions in the job named setup. Set a trigger to run the workflow on push to the main branch and ignore tags – because we will use actions-bot to push tags directly onto the main.

# ci-cd.yml

name: CI/*CD*

on:

push:

branches:

- main

tags-ignore:

- '*'

paths-ignore:

- 'package.json'

- 'pnpm-lock.yaml'

- 'CHANGELOG.md'

jobs:

setup:

if: |

echo "Your condition here"

name: Get engines

outputs:

NODE_VERSION: ${{ steps.env_vars.outputs.NODE_VERSION }}

PNPM_VERSION: ${{ steps.env_vars.outputs.PNPM_VERSION }}

RELEASABLE: ${{ your condition here }}

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

uses: actions/checkout@v3

- name: Set ENV variables

id: env_vars

run: |

echo "NODE_VERSION=$(jq -r .engines.node ./package.json)" >> $GITHUB_OUTPUT

echo "PNPM_VERSION=$(jq -r .engines.pnpm ./package.json)" >> $GITHUB_OUTPUT

# ...Versioning is accomplished using npm package standard-version that follows the conventional commits specification and bumps version based on the commit message. Because I had it installed in the project, I chose not to use their open-source action, but the package itself by running a set of commands. Here’s how I made it work.

# ci-cd.yml

# ...

jobs:

setup:

outputs:

NODE_VERSION: 18.12.1

PNPM_VERSION: 7.25.0

RELEASABLE: true

# ...

version:

name: Bump Version and Git Tag

env:

NODE_VERSION: ${{ needs.setup.outputs.NODE_VERSION }}

outputs:

APP_VERSION: ${{ steps.app_version.outputs.APP_VERSION }}

needs: setup

if: |

needs.setup.result == 'success' &&

needs.setup.outputs.RELEASABLE == 'true'

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

uses: actions/checkout@v3

- name: Use Node.js (${{ env.NODE_VERSION }})

uses: actions/setup-node@v3

with:

node-version: ${{ env.NODE_VERSION }}

- name: Checkout main

uses: actions/checkout@main

with:

fetch-depth: 0

token: ${{ secrets.ACTIONS_BOT_ACCESS_TOKEN }}

- name: Configure committer

run: |

git config user.name "actions-bot"

git config user.email "project.account@symphony.is"

- name: Run standard-version

run: |

npx standard-version

git push --follow-tags origin main

- name: Output App Version

id: app_version

run: |

echo "APP_VERSION=$(jq -r .version ./package.json)" >> $GITHUB_OUTPUT

# ...We’re outputting the app version in the last step of the version job and that output will be passed to the next job build-and-deploy-dev that uses the reusable workflow build-and-deploy.yml.

In this case, Firebase is being used as a hosting platform, thus the service account secret is saved in the Github actions repository secrets. Also, this workflow can be triggered manually on workflow_dispatch or in this case on workflow_call as a part of the pipeline.

# ci-cd.yml

# ...

jobs:

setup:

outputs:

NODE_VERSION: 18.12.1

PNPM_VERSION: 7.25.0

RELEASABLE: true

# ...

version:

outputs:

APP_VERSION: 1.2.0

# ...

build-and-deploy-dev:

name: DEVELOPMENT

uses: ./.github/workflows/build-and-deploy.yml

needs:

- setup

- version

with:

version: ${{ needs.version.outputs.APP_VERSION }}

environment: dev

nodeVersion: ${{ needs.setup.outputs.NODE_VERSION }}

pnpmVersion: ${{ needs.setup.outputs.PNPM_VERSION }}

secrets:

FIREBASE_SERVICE_ACCOUNT_DEV: '${{ secrets.FIREBASE_SERVICE_ACCOUNT_DEV }}'Deploy-to-production job looks exactly the same except environment (prod) and service account secrets differ from the original. That is, in case you decide to conduct continuous deployment. However, don’t forget to feature-flag new changes because you don’t want end-users to do quality assurance before you. 😀

My Point of View

If it fits in one blog post, it probably isn’t that hard to implement tech-wise. Other than that, proper conduction of TBD on a project requires a well-formed agile team. In other words, your team must have strong communication and a high level of transparency in order for this to work.

My experience tells me that one brings out the other. Once the team gets used to TBD, it comes naturally for people to communicate better and more transparently in agile meetings.

© Copyright Notice

This article has originally been published on Symphony.is.